Uncertainty is a mental state. We view it through our own subjective, cognitive lens. Technically, it is based on ignorance but it is not mere ignorance. As Eric Anderson and colleagues describe in a fascinating Frontiers in Psychology paper in 2019, uncertainty is the conscious awareness and experience of ignorance. In other words, we’re certain that there’s something important going on that we do not understand.

This state of being is now prevalent. In the world around us we see inflation, a war in Ukraine, global supply issues and environmental catastrophes; in our everyday lives we experience the rapid emergence of disruptive technologies and changes in the way we work.

How we experience uncertainty – and why we hate it

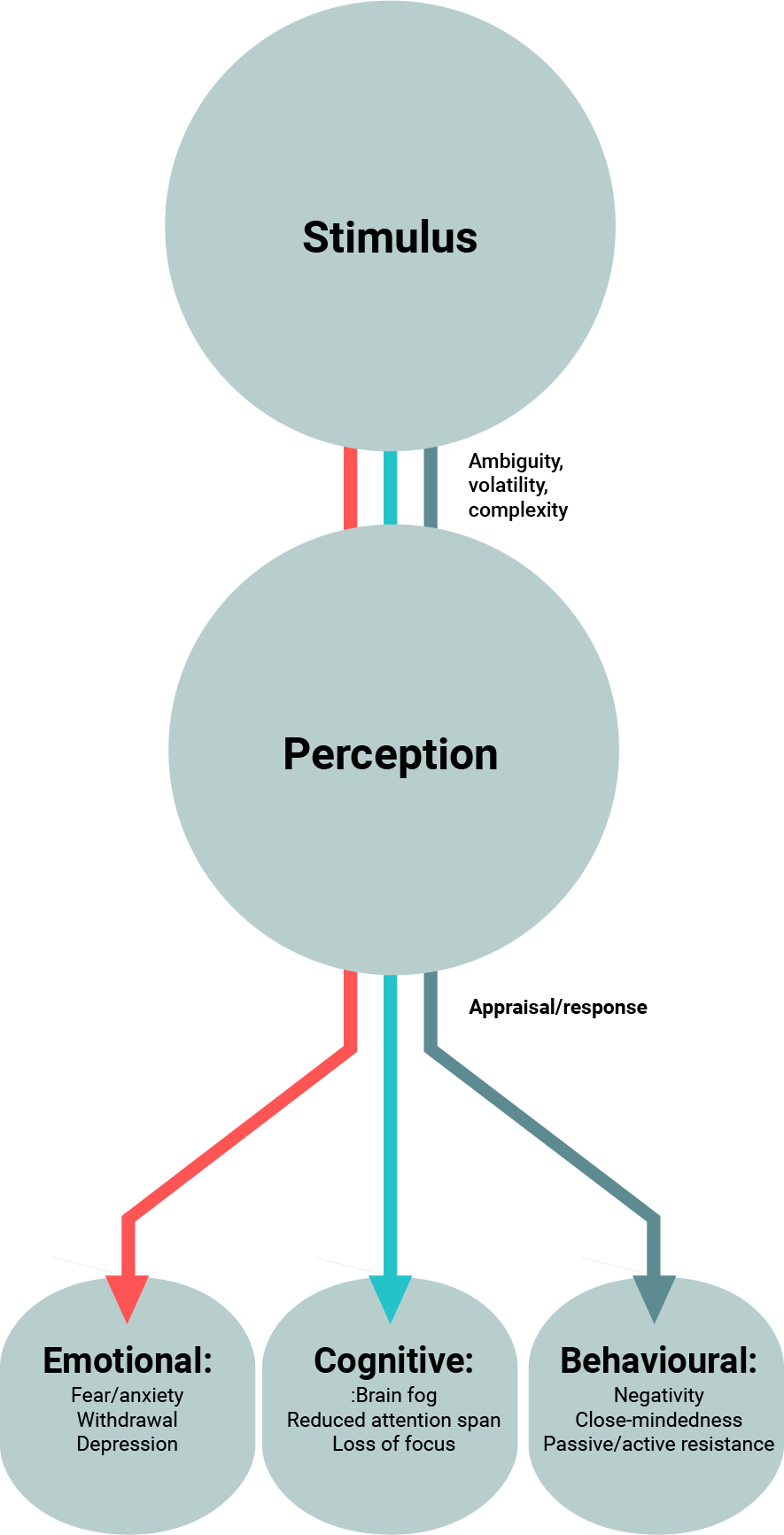

The leading behavioural scientist Paul Han has identified three types of sources of uncertainty:

- Probability (or risk) - this arises from an indeterminate or random future

- Ambiguity - a result of potentially unreliable, uncredible or inadequate information

- Complexity – when an issue is difficult to comprehend

Right now people are experiencing all three at the same time – but we have a finite capacity for it.

Humans are pattern-seeking beings. We're constantly looking for the world to fit what we're seeing, what we're experiencing, even subconsciously fit it into something familiar that we've already got stored within our brain

Dr Zara Whysall, business psychologist and associate professor at Nottingham Business School

Right now, people are experiencing all three types of uncertainty at the same time – but, as business psychologist and associate professor at Nottingham Business School Zara Whysall says, we have a finite capacity for it.

Dr Zara Whysall, business psychologist and associate professor at Nottingham Business School

“When the brain comes across new information, it uses pattern-recognition to try to match the information received with what’s already stored in the brain. With experience, certain patterns get honed or ‘primed’ so that they’re more easily recognised; essentially this is why experts are better at things, over time; their experience (or practice) hones the connections or patterns in the brain, in terms of certain things (chunks of information) relate to one another.

“With experience we spot these patterns really easily, it becomes rapid, intuitive, second nature. When something doesn’t fit in with this, we either don’t notice it – our attentional system ‘glosses over’ it or filters it out.”

In this environment, we look for the answer that takes the least amount of energy to process. We want to keep things cognitively simple. The superstar psychologist Daniel Kahneman talks about System 1 and System 2 thinking. System 1 is the intuitive, largely unconscious thinking that goes on in the brain constantly. It’s the brain’s autopilot, keeping us running without diverting our attention. It accounts for 98% of our thinking.

System 2 is for environmental factors that require our conscious attention. This is a much more energy-intensive cognitive process. It takes up 2% of our thinking. Our brains look to “solve” System 2 issues and move on, to conserve energy for other things. This creates a bias towards the familiar, and leaves us with blind spots.

There's evidence about doctors looking at scans: if you put something completely random on a scan that shouldn't be there at all, such as a very small picture of an animal, they will completely miss it because it's not something that you might usually see. It doesn't fit the mould.

Dr Zara Whysall, business psychologist and associate professor at Nottingham Business School

The problem for managers and leaders is that people can get overwhelmed by uncertainty. How quickly depends on their cognitive capacity for change. “It’s why a lot of talent selection involves cognitive ability tests these days,” says Whysall. “Cognitive ability is an important predictor of performance in many jobs, and particularly in leadership, where you have to consider multiple sources of information.”

Dr Lynda Folan, an organisational psychologist

Certain personalities find disruption extremely difficult to deal with and will crash faster than others, says Dr Lynda Folan, an organisational psychologist whose doctoral research informed her book Leader Resilience. “Everything filters through your personality, your values and experiences. If that filtration system is slightly dysfunctional, you're going to fall over more quickly.”

When this happens in management and leadership, you tend to see “a massive degradation in culture,” says Folan. “You’ll start to see people shutting down because they don’t feel safe.” Sometimes leaders may have unconsciously caused the response themselves.

People who hit that cognitive limit for volatility will become more negative, explains Dr Carolyn Lorian, head of clinical transformation at Silvercloud Health, which provides digital mental health services for the NHS. They may not process information properly and won’t be able to concentrate. “Someone who was a high performer may no longer deliver at the same level, or might struggle to retain information or juggle multiple things.”

Worst cases, this will fuel anxiety and depression. You may see what’s called “hyper arousal” as an immediate response but this can’t be sustained for any significant period of time. People try to plumb their resources, which become depleted. The result is low mood fatigue, burn-out, and depression. Emotional contagion follows, spreading negativity and mental ill health like a virus through the organisation or community.

Let's fix this

More from CMI

But there is another way. As we explore in this edition of the CMI Magazine, even in a climate of profound uncertainty and volatility, good managers can deliver certainty through clear, consistent goals. Zara Whysall describes this as “fix the vision, flex the journey.

Dr Carolyn Lorian, an organisational psychologist

People’s capacity for change and ability to withstand volatility can’t of course be solved with a single training course. But as volatile conditions continue, organisations and managers must face the challenge head-on.

“Look at the likes of Nokia, the likes of Polaroid; they were really successful brands, but they stopped looking outside,” says Whysall. “They stopped looking at what was changing. And by the time they noticed, it was too late.”

Typical responses to uncertainty